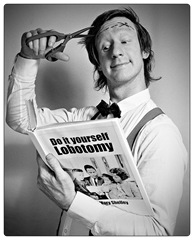

As far as I know, we have two books at the bookshop about lobotomies. One is called My Lobotomy, and is written by Howard Dully, an actual lobotomized man, about his lobotomy, lobotomy. His frontal lobe was removed at his stepmother's behest and to his surprise. He was a bad kid with deplorable table manners, so a doctor who drove a car called "The Lobotomobile" scrambled up Howard's lobe at age twelve (sorry if this is disgusting) to make him better (for just $200). I didn't read far enough to find out how he turned out, but it seems that he still has a lot of anger, and chapter 12 is entitled "Homeless," which doesn't bode well.

As far as I know, we have two books at the bookshop about lobotomies. One is called My Lobotomy, and is written by Howard Dully, an actual lobotomized man, about his lobotomy, lobotomy. His frontal lobe was removed at his stepmother's behest and to his surprise. He was a bad kid with deplorable table manners, so a doctor who drove a car called "The Lobotomobile" scrambled up Howard's lobe at age twelve (sorry if this is disgusting) to make him better (for just $200). I didn't read far enough to find out how he turned out, but it seems that he still has a lot of anger, and chapter 12 is entitled "Homeless," which doesn't bode well. Our second lobotomy book is called The Ice Pick Technique and was written by someone named Anna Mavrikis, who does not admit to having a lobotomy. It is a tale of greed, egomania, and lobotomies. The two practitioners end up accidentally murdering people with their ice pick. Go figure.